Icy Qiao is a London-based multidisciplinary artist working across animation, moving image, sculpture, and installation. Her practice is deeply autobiographical, exploring trauma, identity, and East Asian family dynamics through emotionally charged, experimental storytelling.

A graduate of the Royal College of Art’s Narrative Animation program, Icy transforms memory and psychological experience into tactile, visual forms. In 2023, her work was permanently collected by a national first-tier museum in China, cementing her growing presence in both international and domestic art scenes. Here is our interview with Icy Qiao.

How does giving shape to anxiety, like your clay tooth sculptures, change the way you carry it?

I keep a habit of journaling at night and recording dreams in the morning as a form of self-analysis. Later on, when I checked my records, I found out that during anxious periods, I repeatedly dreamt of teeth falling out, sometimes lost, sometimes swallowed. I began sculpting those teeth in clay. The tactile and slightly unruly material let me retrieve what the dream had taken. The act echoed Melanie Klein’s idea of aggression and repair. In the dream, I swallowed my aggression; in waking life, I carefully rebuilt it. Externalising it clarified the source of my anxiety, unexpressed anger and blurred boundaries, and it reduced the intensity.

Your work avoids traditional stories in favor of fragments. What does breaking narrative open up for you?

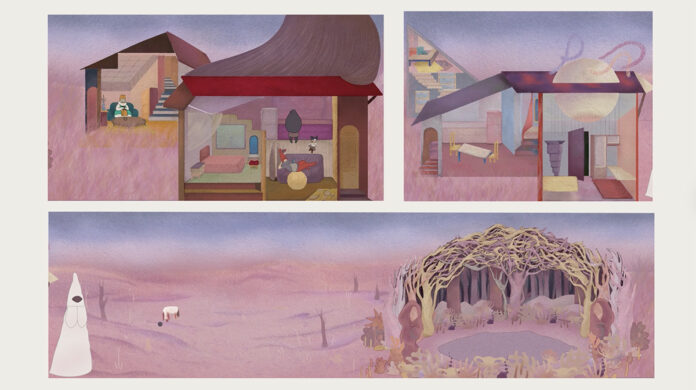

I’m drawn to nonlinear and multi-threaded storytelling. Traditional narrative structures often feel a bit dull to me—they focus so much on clarity and technical execution that I start paying more attention to form than feeling. That’s why I’m always curious about how to break those structures. In my piece Self-Inflicted Pain, for example, I wanted to explore whether emotion could be conveyed purely through image, without relying on plot or voiceover. The film consists of six actions with no specific storyline, emphasising the repeated weight of traumatic memory.

In another piece, Eleven, an immersive storytelling work, I placed multiple characters with individual storylines throughout a space. I wanted viewers to explore freely rather than be guided by a single viewpoint or traditional montage. These experiments help me rediscover other possibilities of moving image, beyond narrative, toward atmosphere and emotion.

Silence seems to echo through your pieces. How has growing up in East Asian family dynamics shaped how you express emotion?

I’ve never been someone who’s good at expressing emotions verbally. I grew up in an environment of emotional neglect, a typical East Asian household structure with an absent father and an over-controlling mother. My mother and I formed an unhealthy codependent relationship where my emotions and identity were often consumed or dismissed. Over time, I became used to silence.

This silence naturally found its way into my work. Art became the outlet for everything I couldn’t say aloud. I’m drawn to the process of creating something out of nothing. I rarely use dialogue or text in my pieces, I see the work itself as its own language. I prefer viewers to experience the emotions through their own lens.

When you return to the same themes or actions, is it for comfort, control, or something else entirely?

There’s a psychological method called trauma reprocessing therapy, and in many ways, my work reflects that. Much of what I create revolves around memory and trauma. By revisiting and reconstructing those scenes, I reframe their meaning and build a stronger sense of control over them.

This process also allows me to reconnect with the version of myself that felt helpless—someone I had once abandoned. Through empathy and care, I begin to reintegrate her. So yes, there’s comfort, and there’s control, but above all, it’s about healing. It’s a rebirth of self.

Your pieces are deeply personal, but also speak to bigger cultural issues. Where does your story end and something collective begin?

My creative process always starts from personal experience. It’s a matter of sincerity, I find it difficult to speak authentically about things I haven’t lived. But from that starting point, I often research whether my experiences reflect broader social or cultural patterns.

For instance, my 2D animated film MoM explored toxic symbiosis in intimate relationships—both familial and romantic. It stemmed from my relationship with my mother, but the film uses a symbolic character rather than a literal representation. I wanted the “object” of the relationship to be interchangeable, to reflect how in codependent dynamics, the other is often treated as a possession. This is especially common in traditional Chinese households, where emotional roles are inverted.

While I sometimes worry my work is too introspective, I believe people with similar lived experiences can still find resonance in it. That’s where the personal begins to connect with the collective.

Across sculpture, film, and installation, how do you know which medium a feeling belongs to?

Often it comes down to intuition. I keep a note on my phone where I jot down fleeting ideas, and I revisit it regularly to see if any recurring feelings or images could evolve into a full project.

I don’t like being confined by a medium. I prefer to engage all my senses when brainstorming. For example, one project I’m developing currently comes from a childhood memory. I lived next to a road, and at night, I’d stare at the ceiling as car lights flickered through the curtains, casting lights that would grow and shrink before fading away. That rhythm, the appearance and disappearance, reminds me of how relationships come and go in life. I want to express that through light and sound installation to recreate the environment.

In Eleven, I used a fabric sculpture to represent my grandmother, my ivory tower. The material was an old bedsheet, because as a child I believed beds and blankets had magical powers to protect me. Holding that sculpture gave me a strong sense of safety.

Each work is guided by emotion. The medium just follows naturally, based on which elements can best reflect that emotional core.

When it comes to future projects, what are you currently working on?

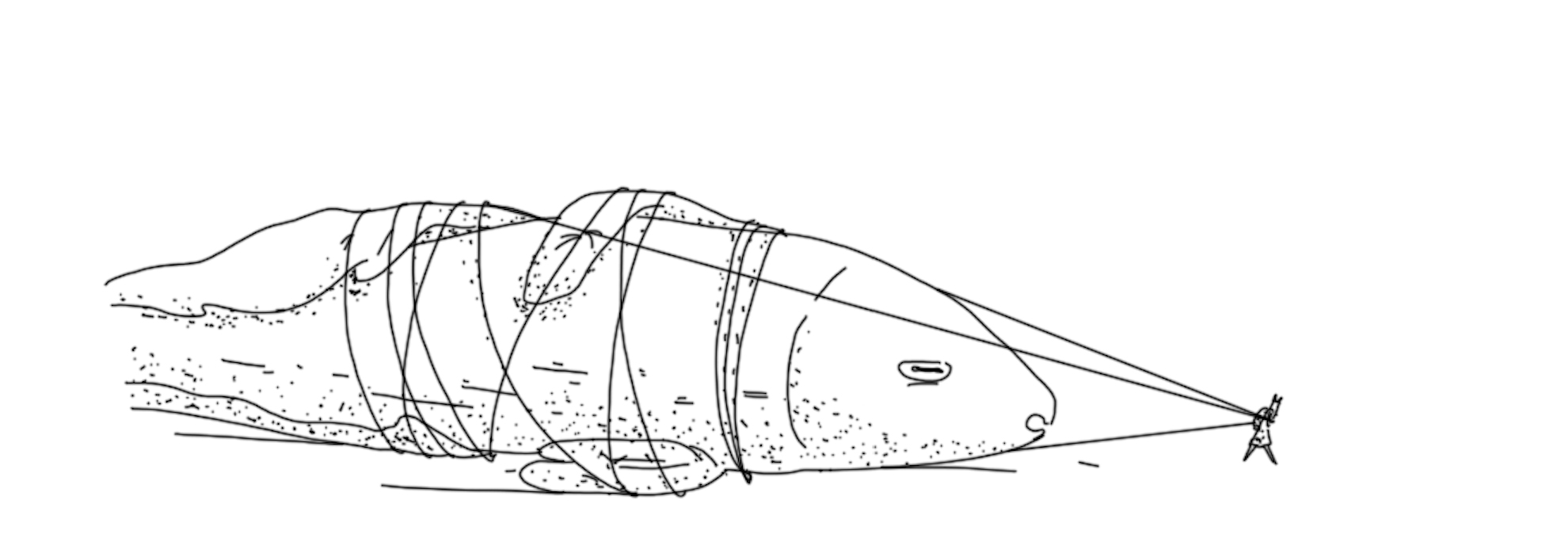

I have several ideas in development. Aside from the installation I mentioned, I’m also working on an experimental project called Restless Animus. The name comes from Carl Jung’s theory of the anima and animus—gendered soul archetypes that represent our unconscious complement.

The idea first came up during a therapy session where I was asked to visualise my current state in a meditative way. The image that came to me was a shattered glass cup held together inside a protective layer of delivery foam. That foam, for me, represented the support systems around me—friends, family, people who care. It created a sense of relative stability: not solid or permanent, but just enough to hold the fragments in place. This fragile balance felt true to my current psychological state, externally supported, yet internally fractured. Even within that cushion of care, the essence inside remained restless and unstable. That tension between appearing held together and actually being in pieces is what I want to explore further. I imagine my future work will go deeper into these inner layers.